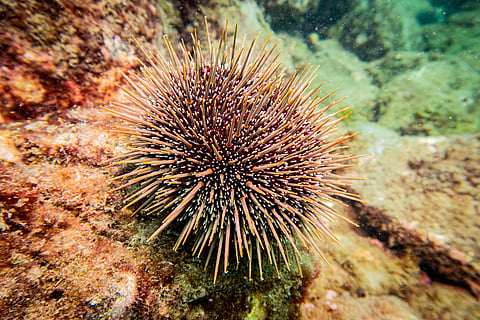

Kina is the name given to the native sea urchins of New Zealand. Overpopulation of this species is wiping out kelp forests and, with them, entire ecosystems.

Photo: Adobe Stock.

Kina barrens occur in more areas along the New Zealand coast, but the problem is most acute on the east coast of the upper North Island. Fisheries New Zealand is seeking solutions and has opened a consultation period on two proposed measures to help address the problem and rebalance local ecosystems in this area.

The proposals include a new special permit for targeted culling, harvest, or translocation of kina and long-spined sea urchins, and options to increase recreational daily bag limits for kina in the Auckland East Fisheries Management Area, and submissions can be made online until 5 pm on 3 May 2024. However, the country has already given aquaculture a chance to solve this problem.

"Kina barrens are areas of rocky reef where healthy kelp forests have been consumed by an excess of kina to form a bare, or barren, space, making it uninviting to other marine life," explains Emma Taylor, Director of Fisheries Management at the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) of New Zealand.

A slightly longer explanation can be found in Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. "Native sea urchins (kina) are important grazers in forests of kelp. At times, hordes of kina may strip a reef of kelp, creating an open area known as a barren. Young kelp that try to colonise the open area are devoured by resident kina, and a barren may remain free of large seaweeds for years."

But how do these "hordes of kina" come to be there? For a variety of reasons, ranging from overfishing to climate change and natural phenomena such as tsunamis, the natural predators of these sea urchins - such as crayfish and big snapper in New Zealand, for example - have disappeared. As a result, kina are reproducing uncontrollably and eating up all the kelp forests.

"Kelp forms a key part of a healthy ecosystem in these areas and promotes biodiversity by offering shelter, breeding grounds, and food sources for a range of sea life, including kina predator species," Emma Taylor continues.

The special permit proposed by Fisheries New Zealand would allow the removal of kina and long-spined sea urchins from both areas where urchin barrens already exist and those that are at risk of forming new ones. These special permits would also allow kina to be moved to other areas with low sea urchin densities to improve their food value or for use in aquaculture projects.

The second proposed measure is to increase the daily catch limit in the East Auckland fisheries management area, which covers the east coast of Northland, the Hauraki Gulf, Coromandel, and the Bay of Plenty. The current daily catch limit for kina is 50 per fisherman, and the proposed options are to increase this limit to 100 or 150 per fisher/day.

"Although targeted removal and increased daily bag limits aren’t a silver bullet for kina barrens, these measures will play an important role in the recovery of kelp in marine ecosystems that are suffering from too much kina," New Zealand Director of Fisheries Management argued.

As said above, kina barrens occur in other regions of New Zealand, however, they are most prevalent along the east coast of the upper North Island. "Raising the daily bag limit for this area aligns with the localised nature of the issue and aims to address the specific challenges of the region," explains Emma Taylor.

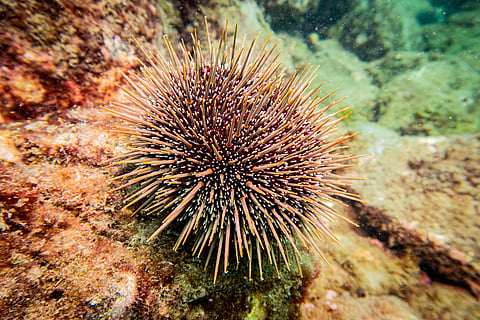

Empty, barren urchin (left) and ranched urchin (right) from Urchinomics land-based aquaculture.

Photo: Urchinomics.

Although these proposals only talk about catch, solutions for kina barrens are also being tested in New Zealand using aquaculture as a tool for job creation while supporting the restoration of kelp forests and marine ecosystems.

Last year saw the launch of Kinanomics, a joint project between Evirostat, Ngati Porou Seafoods Groups, and Urchinomics - the pioneering restorative aquaculture company that aims to turn ecologically destructive sea urchins into high-value seafood products - whose objective is to create a high-value aquaculture industry in New Zealand from the kina barrens.

Like its predecessor Uchinomics, Kinanomics is a restorative aquaculture venture to turn an environmental challenge into an economic, ecological, and social opportunity. So explained Urchinomics founder and former CEO Brian Tsuyoshi Takeda to WeAreAquaculture in his TalentView interview.

"In short, we pay commercial fishers to harvest empty urchins that are preventing kelp forests from growing and put them into our land-based recirculating systems. We then feed them a naturally derived formulated feed, and turn them into premium sea urchin roe, or 'uni', in 6 to 12 weeks. And, as a result of removing urchins from the seafloor, we help kelp forests recover."

Precisely in that same interview, talking about the challenges that Urchinomics and its business model could face in the future, Takeda explained that, curiously or contradictorily, the first of all were the conservationist regulations adopted by governments in the past. Back in the 80s, when Japan was roaring, there were fears that Japanese consumption would deplete sea urchin stocks around the world, so various governments implemented regulations to prevent overexploitation.

"Catch size limitations and fisheries closures were put into place to preserve stocks. However, now that urchins have overrun so many places around the world, the problem is not overexploitation anymore but rather too many urchins overgrazing kelp forests. Those rules, put in place with good intention to protect stocks, are now ironically the same rules preventing kelp forest restoration," he told WeAreAquaculture.

This explanation helps to understand why Fisheries New Zealand is now making such concrete proposals. Eliminating sea urchins from certain areas - even when they are empty - or fishing more than the fifty kina allowed are logical solutions that, however, are currently in conflict with the established regulations, and that is why they must now be taken to public consultation.

In that interview, Brian Tsuyoshi Takeda appealed to governments to create a separate type of permit, a kind of restorative aquaculture permit, which would allow fishing for urchins of all sizes, all year round, in designated areas. Now, New Zealand - a country more and more committed to aquaculture, with projects such as the super snapper or plans such as those in the Southland or Waikato regions - is asking its citizens to help decide on the kina barrens management.

Given that we are talking about a problem that, to a greater or lesser extent, occurs globally, it is likely that New Zealand will not be the last country where we will see something like this: new environmental restoration versus outdated conservationist regulations.