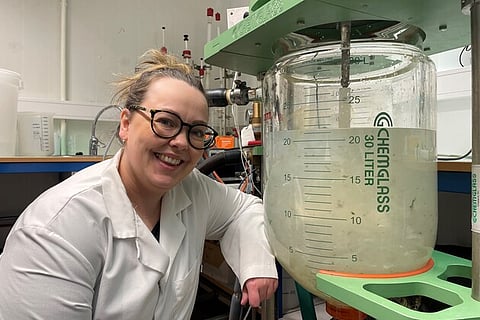

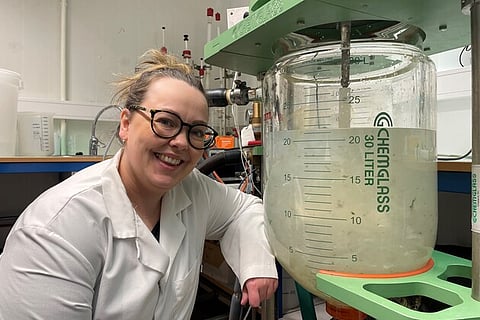

Using techniques such as hydrolysis, Nofima researcher Marte Jenssen and her colleagues can turn the waste from whitefish into new, valuable products.

Photo: Anne-May Johansen, Nofima

Norway could produce more food, cut waste and create new jobs by making better use of offal from whitefish such as cod and haddock, according to Norwegian research institute Nofima. The institute argues that by-products from the fishing industry remain underused, particularly by the Norwegian long-distance fleet.

Researcher Marte Jenssen said that material once considered worthless now represents an untapped source of nutrients. “The offal is valuable. We’re talking about a high content of nutrients the body needs, among them proteins, healthy fats and important vitamins,” she explained, via a Nofima news release.

Jenssen, together with colleague Lars Dalheim, has authored a new Nofima report, funded by the Norwegian Seafood Research Fund (FHF), finding that offal and entrails made up 55% of whitefish by-products in 2024. While coastal vessels retain most of this material, ocean-going boats use only around 43%, according to the institute. As a result, large quantities of usable raw material are discarded at sea before the fish are landed. However, the researchers suggest, better processing could “mean a large increase in value creation and sustainability.”

The report is part of a larger research project - TOPP - exploring how cod milt can be processed into oil and protein products. Nofima researchers, working with NTNU, NUAS Technology and Nord-Senja Fisk, recently carried out a pilot production at Nofima’s Biotep bioprocessing plant, with the results now under analysis.

Norway already has technology to preserve these byproducts, the researchers argue, with significant potential to turn more of this "waste" material into products for human consumption.

“What we can extract from the offal are nutrients that can be used for high-value products such as food ingredients, dietary supplements, biomedical products and cosmetics. And also for feed ingredients and even packaging products,” Jenssen said.

To achieve this, the researchers argue that vessels operating far from shore need better systems to handle and store by-products. Jenssen said there have been several recent political initiatives aimed at improving utilisation, both to supply more food globally and to strengthen the seafood industry while cutting food waste.

“We have both the knowledge and the equipment that are needed. It is just a matter of ensuring it becomes economically attractive and practically feasible to do it,” she said.

Nofima noted that certain parts of cod, such as liver and roe, are already used for food or cod-liver oil, but that utilisation varies widely between species and fish parts. The institute suggested that automatic sorting of offal fractions, such as liver, intestines and roe or milt, could reduce waste and increase returns.

The report acknowledges that beyond the technical challenges, lie potential obstacles in regulation and consumer attitudes. “The challenges lie in attitudes, market development and regulations. By-products are not always popular among consumers, and it can be complicated and expensive to process the offal into products that are safe, smell pleasant and taste good,” said Jenssen. She also noted that marketing such products with health claims can be difficult under current rules.

However, the researchers also pointed out that countries like Iceland have advanced further in using whitefish more efficiently, processing more parts of the fish for high-value food products and export markets.

The goal, the researchers say, is that as much of the by-products as possible should contribute to value creation and that all edible material should be used for human consumption. The rest, they propose, could also be turned to good use, with potential for feed, biogas or industrial inputs.